After the interruption of the Second World War economic recovery was slow. There was a surge of demand for bikes as a means of personal transport. It was short lived, once employment recovered bikes were displaced by motorbikes and cars. The market for bikes declined, interest in the traditional time-trial format of cycle sport established in Britain fell into the doldrums. But a the seeds of a resurgence were taking root. Slowly at first, and not without controversy, interest and participation grew in massed-start road racing. The groundwork was being laid for Britains dominance of road and track racing 60 years later.1945-6 Britain had ‘won’ WW2. There had been tremendous technological advances in this effort, at the expense of the living standards of the nation. Four and a half million servicemen were then de-mobilised. Their euphoria was quickly dispelled. Britain was in hock to the USA, it soon had to relinquish its empire; the USA was the new industrial and technical superpower. The heroes returned to shattered cities, a crumbling rail service, a bankrupt economy, food and petrol rationing. The demand for bikes soared – they were for most the only affordable means of transport until car ownership gathered pace at the end of the decade.

![]() faced a re-start. Islington was in ruins. Frank re-opened his business in Kingston-on-Thames, close to his Teddington home and spent the rest of his working life there. At first he may have seen this as a temporary expedient while the bomb shattered Islington area was rebuilt – his bikes still sported the pre-war ’43 Penton St’ address. However, the new Carpenter shop quickly became established as the centre of sporting cyclists in the area and was well known for its friendly atmosphere. Mrs Carpenter ran the shop’s administration and kept detailed records in her precise handwriting. She also ran a “book” for the younger riders, enabling them to buy equipment by spreading repayments over a period of time. Known as “Mrs C”, she was liked and admired by all who dealt with the shop.

faced a re-start. Islington was in ruins. Frank re-opened his business in Kingston-on-Thames, close to his Teddington home and spent the rest of his working life there. At first he may have seen this as a temporary expedient while the bomb shattered Islington area was rebuilt – his bikes still sported the pre-war ’43 Penton St’ address. However, the new Carpenter shop quickly became established as the centre of sporting cyclists in the area and was well known for its friendly atmosphere. Mrs Carpenter ran the shop’s administration and kept detailed records in her precise handwriting. She also ran a “book” for the younger riders, enabling them to buy equipment by spreading repayments over a period of time. Known as “Mrs C”, she was liked and admired by all who dealt with the shop.

Frank was regarded with some awe and respected for his fanatical attention to detail. He often offered advice and guidance to young riders and had ridden competitively in his younger days. However, he could be a little feisty if materials delivered to him or any sub-contracted work was not up to his high standards.

One man who supplied Frank (among others) with prepared lugs in this period was Ken Janes. Fancy-lugged Carpenters from the immediate post-war era quite possibly exhibited Ken’s work. He went on to be the skilled craftsman behind Hetchin’s famed decorative lugwork. Frank C kept a good stock of lugs, so possibly those on #4908 (abt. 1955) are an example.

Reynolds, faced with the sharp reduction in aircraft production, returned to the cycle market. 531 tubesets were again in supply. Through their subsidiary High Duty Alloys they also returned to offering forged RR56 components – marketed as ‘Hiduminium’. These handlebars, stems & seatpins now gained the trust of racing men. “If it was good enough for the Spitfire…”

Gerry Burgess launched GB Ltd., offering Hiduminium brakes (Calliper arms forged by Reynolds) as well as bars. Stems were 531 steel at first, soon superseded by forged Hiduminium as confidence in this material grew.

1946 TV broadcasts resumed, then were briefly suspended during the 1947 fuel crisis. George Formby was awarded an OBE. His jaunty ukulele and risqué lyrics had helped keep the nation’s pecker up through the dark years.

1947-56 The economy may have been depressed, but technologies advance by the war effort delivered Britain world speed records on land, on water and in the air.

Unfortunately the development of British cycle component designs had stagnated. Hardly a priority during the war, in peacetime the BLRC was still in its infancy. Traditional time-trialling still dominated the UK so there was still too small a market to provide any incentive to producers. It was different on the Continent….

1948  Gino Bartali won seven stages of the Tour de France, gaining the Mountains prize. He rode into Paris for his second General Classification win, for the first time confronted by TV cameras.

Gino Bartali won seven stages of the Tour de France, gaining the Mountains prize. He rode into Paris for his second General Classification win, for the first time confronted by TV cameras.

The question of gears. Bartali’s Campagnolo Cambio Corsa race gearing looks cumbersome now but delivered a competitive edge at the time. However, Simplex’s ‘Tour de France’ derailleur was in the ascendant, a cage of two jockey-wheels (so familiar now) controlled by a chain-pulled plunger-spring (an obsolete method now).

1949 Tullio Campagnolo refined the two-levered Cambio Corsa gear and patented his ingenious but ridiculous ‘Uno-Leve’ gear change mechanism (later re-branded ‘Paris Roubaix’ after Fausto Coppi won that pan-flat race using this gear – as seldom as possible?? ).

The Eastern Bloc countries established the Berlin-Warsaw-Prague ‘Peace Race‘ as an ‘amateur’ counter to the professional tours of France, Italy and Spain.

London stepped in at short notice to host the Olympic Games after Rome pulled out. No new venues were built for these “austerity” games. British athletes, living on restricted rations, envied the diets of their USA competitors, and in general disappointed. These were the first games to be televised, though only in the London area. Track cycling was held at Herne Hill, road cycling took place in Windsor Great Park.

Soon after these games Frank Carpenter stopped using up his old stock of pre-war ‘Penton Street’ brass head badges and introduced a new one sporting the olympic rings (upside down!). The motivation may have been his rival Claud Butler doing likewise, but Frank Carpenter’s justification for using the rings is unknown. It has been reported that he built wheels for Reg Harris, this may be the only link.

By 1950 there were still only 2 million cars on Britain’s road – now there are 32m.

1950 The question of gears: Tullio Campagnolo saw the light. He abandoned his idiosyncratic ‘Paris Roubaix’ striker plate gear changer. However, he was determined to provide a better solution than Simplex’s plunger-spring mechanism. Instead he refined the parallelogram design with the patent for his Gran Sport mech . Launched the next year it was used by Coppi to win the Tour de France and proved an instant world-beater, rapidly displaced plunger-spring designs. All today’s rear mechs are refinements of the Campagnolo Gran Sport.

1951 The Festival of Britain was organised to showcase Britain’s products to the world. Frank Carpenter helped re-form the Unicorn Road Club as the Festival Road Club – his shop became its unofficial second clubroom. Frank was president of the club for many years from 1954

1952 National TV coverage was achieved in Britain.

Ian Steel won the Peace Race, a BLRC team won the team title. There was little publicity at home.

1953 Enough TV sets had been sold for 20m to watch the Coronation, most by crowding around neighbours’ sets.

For the first time a stage of the Tour de France was broadcast in France on live TV – they saw Fausto Coppi’s ascent of the Alpe d’Huez in a remarkable (and Tour-winning) 45:22. From this point on sports would be enjoyed inexpensively from the comfort of home rather than by paying at the stadium gate. Attendance at velodromes fell away but sports that could command a big TV audience had huge riches in store.

In France’s Grand Prix des Nations, 19 year-old Jacques Anquetil comprehensively beat British time-trial specialists Ken Joy and Bob Maitland.

The question of gears continued. Jack Manning used his ‘Cocoa-Tin’ hub-geared Carpenter #4146 to set new Charlotteville CC club records from 25 miles to 12 hours and was 17th in the national BAR.

The question of gears continued. Jack Manning used his ‘Cocoa-Tin’ hub-geared Carpenter #4146 to set new Charlotteville CC club records from 25 miles to 12 hours and was 17th in the national BAR.

Keith Mitchell’s recollections of this period are here.

Fausto Coppi went on to win the world road-race championship in Lugano using Campagnolo Gran Sport gears. His time was identical to the 2013 race over the same distance and similar terrain – but today’s peleton rides over much better surfaces, on more technically advanced bikes and practices more concerted team-work.

1954 22-Feb. Henry Carpenter, living in Hook, died in Epsom hospital aged 81. His death certificate records him still as a Silver Stick Mounter. It seems his family were still more proud of this skill than his achievements building a nationally renowned maker of specialist race bikes.

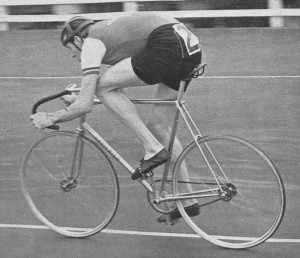

1955-6 Mike Gambrill, Clarence Wheelers, became Carpenter’s most successful rider. With Alan Killick he set new tandem records at 30 and 50 miles, won the National 25-mile title, the National 4000m track Pursuit title and a bronze medal in the Melbourne Olympics team pursuit. Fuller details are here.

1955-6 Mike Gambrill, Clarence Wheelers, became Carpenter’s most successful rider. With Alan Killick he set new tandem records at 30 and 50 miles, won the National 25-mile title, the National 4000m track Pursuit title and a bronze medal in the Melbourne Olympics team pursuit. Fuller details are here.

In 1955 Bill Haley and the Comets heralded a big shake-up in popular music. “Rock Around the Clock” was the best selling number of the decade. in 1956 Elvis Presley had his first chart hit with “Heartbreak Hotel”.

late 1950s through 1960s. With car ownership growing fast, the demand for cycles dropped away – and with it the membership of cycling clubs. These were lean times for the artisan builders.

The nation was gripped by the threat of the ‘Cold War’.

Mid-1950’s With the Cold War at its frosty height (depth?) Britain’s world-leading aircraft industry produced V-bombers, then the Blue-Streak approach missile to deliver its independently developed atomic warheads, the Black Knight ballistic missile in 1958, then finally the Black Arrow launch rocket to enter the ‘space race’. To no avail – this level of spending was unsustainable in peace time. Less militaristic (and longer lasting) was the innovative hovercraft patented by Sir Christopher Cockerell in 1955.

1956 The world’s first nuclear power station opened at Calder Hall. One year later the North of England was saved from the Chernobyl-scaled fallout of a disastrous fire by chimney filters that had been installed at Sir John Cockroft’s insistence.

1957 Jacques Anquetil – ‘Monsieur Chrono’ – won his first of 5 Tours de France

1957 At the celebrated Sciacchi meeting at Herne Hill Mike and Robin Gambrill used a Carpenter tandem to set a new national 5-mile record. 1958 with Alan Jacob (Clarence Wh.) they won the team prize in the national 25 champs. Later, Mike rode away from a strong field to win the classic London-Brighton road race. 1959 Mike Gambrill teamed with Norman Shiel to win the 40k Dresden Madison in 51:41.

1957 At the celebrated Sciacchi meeting at Herne Hill Mike and Robin Gambrill used a Carpenter tandem to set a new national 5-mile record. 1958 with Alan Jacob (Clarence Wh.) they won the team prize in the national 25 champs. Later, Mike rode away from a strong field to win the classic London-Brighton road race. 1959 Mike Gambrill teamed with Norman Shiel to win the 40k Dresden Madison in 51:41.

1959 10m homes had TV by by this date.

The USSR opened the space race by launching Sputnik, the first orbiting satellite.

In its Nov-11 survey of 1960 models, the ‘Comic’ Cycling and Mopeds reports that Carpenter Cycles has received an order from the USA for ‘a quantity of board track machines’. The photo (p11) shows C-L inch-pitch chainring, Brooks saddle, BH Airlite l/f hubs – and an extraordinary UK price of £47.

Beryl Burton won the first of her 25 consecutive Best All Rounder championships, averaging 23.72 mph over 25, 50 and 100 miles – all on fixed gear. British time-trialists still used single speed fixed on their traditional flat courses. Gears had been seen as an aid to touring, but the growth of BLRC road races was changing all that….

1960 Robin Buchan and Mike Gambrill, both using Carpenter track bikes, lapped an international field in a madison in the GDR’s Karl-Marx-Stadt.

1961 Trackman Charlie McCoy set a 25 mile TT record of 55.01, using a 5-speed block. His previous record had been set on fixed wheel.

1962 The United States and the Soviet Union confronted each other over the installation of nuclear missiles in Cuba. Nikita Krushchev blinked first .

The Tornado’s pop hit ‘Telstar’ celebrated the first TV satellite transmissions. A new pop group came home from Hamburg to Liverpool & enjoyed their first hit with ‘Love me do’.

Tom Simpson became the first athlete to emerge from Britain’s track pursuit/timetrial scene to become a top-ranked continental professional, briefly leading the Tour de France.

Dave Bonner eclipsed Charlie McCoy’s 25 mile TT record using Campagnolo Gran Sport gears on his Jensen with 54.28. Time trialists took notice and quickly switched to geared bikes. The fixed gear era was over for most clubmen.

In 1963 Alex Moulton launched his radical F framed bike with 16″ wheels and suspension. After early publicity as a competition mount it found a burgeoning market with those looking for a means of local transport in towns and cities, stylish and modern (much like the Mini, which also incorporated his rubber block suspension). But race bikes remained steel-framed, with lightweight alloy components, 700c wheels and tubular tyres.

1963. 100 of 130 Tour de France riders were equipped with Campagnolo gears. Brooks saddles and Reynolds 531 tubing held sway. Other British component suppliers such as The British Hub Company, Cyclo-Benelux and Williams had responded too late, were never featured in the peleton and were soon to be driven from the market.

1964 The Rolling Stones first No.1 hit “It’s all over now” hit the airwaves. Very apt!

1965 Frank Carpenter displayed #4921 (a 1955 BLRC road bike) for sale second hand. It was purchased on condition it was first fitted with a Campagnolo chainset, gears and hubs. Tellingly, Frank did not stock these, so bought them from Pearsons. For the first time there were signs he was falling ‘behind the curve’ though in fairness he had adopted Campagnolo dropouts in his frames.

1965 Tom Simpson won the world road-race championship. He had progressed from a promising time-trialling teenager to a precocious track pursuit rider before becoming Britain’s best roadman to that date. Britain was no longer a competitive back water, it could indeed compete on the world stage. The country’s integration into the Continental racing scene was moving forward; clubmen increasingly looked abroad for the specifications of their bikes and accessories

1966 32m viewers watched England win the World Cup. One year later the BBC introduced the world’s first colour TV service.

1967 was marked by the tragic death of Tom Simpson, His demise on Mont Ventoux cruelly revealed a darker side of professional cycling.

Bobbi Gibb and Kathrine Switzer defied race officials at the Boston Marathon. Gibb finished in 3hs. 21, Switzer in 4hs. 20. Women were openly challenging men’s exclusive hold on endurance events.

1967 was also the annus mirabilis for Beryl Burton. Frustrated at losing her title as women’s world pursuit champion, she compensated by promptly joining Graham Webb in winning the world road race championship. Uniquely, she was invited to compete against the top pro’s of the era in the Grand Prix des Nations, then later set a new 12 hour record of 277.25 miles, overtaking Mike MacNamara while he was in setting the new men’s mark of 276.52 She famously handed him a liquorice allsort as she passed. Never again could endurance sports be seen as the preserve of men. In the mean time she won her 9th. consecutive “Best All Rounder” title.

On the track, between 1968 and 1973, Hugh Porter won the Professional World 4000m Pursuit championships four times, continuing Britain’s strong performances in this discipline which doubtless stems from the tradition of club riders concentrating on time-trials in their early development.

1968 Dick Fosbury had the courage, skill and determination to develop a radically different way of tackling the high jump. Jumping backwards, head-first, he kept his centre of mass much lower. His reward? Gold and an Olympic record 2.24m at Mexico. Now no other method is used. 23 years later Greg LeMond tackled the TdF time trial with a similarly open mindset – and a similar reward.

Late 1960s Ill health forced Frank to stop frame building. This work was contracted out to Swindon Cycles.

1969, July 20th. was the date Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped off the module of Apollo 11 having made man’s first flight to the moon. This was pretty much exactly 50 years after Alcock and Brown’s transatlantic feat and comparably risky. “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”. Unlike our earlier aviators, their feat was watched live by 750 million TV viewers. These two aviation milestones neatly ‘bookended’ the span of Carpenter bikes and dramatically illustrate the transition of technological leadership from the Old World to the New. Britain was well out of the frame, unable to match the eye-watering costs involved.

1969 Concorde prototypes 001 & 002 flew in Toulouse and Bristol. This was the final flowering of Britain’s wartime aerospace advances. The elegant ‘Ogee’ delta wings were developments of the V-Bombers wings. Its Rolls-Royce engines had been developed from the Olympus engines that powered those bombers. The air intakes learned from the Bloodhound ramjet-powered ground-air missile. This plane could outpace most fighters of its day. Its fuselage was skinned with heat-tolerant Hiduminium. Did Gerry Burgess know?

1971 Robin Buchan, riding his Carpenter road bike, won the CTC (short-distance) BAR with

-

-

-

- 55-07 for 25 miles,

- 1-48-44 for 50

- 4-6-51 for 100

-

-

Buchan was 3rd. in the national BAR and also set a new record winning the national 24-hr champs (483.84 m).

1972, Eddie Merckx ‘the Cannibal’ won Milan-San Remo, Liege-Bastogne-Liege, Giro di Lombardia, two Grand Tours (Giro d’Italia, the Tour de France), then went to Mexico City to tackle Ole Ritter’s hour record on a specially built Colnago bike weighing 5.75 kg. That’s a full 3 kg less than conventional track bikes of the era – see #5767. He covered 49.431 km, a distance only bettered on carbon aero bikes until 2000 when Chris Boardman used a UCI compliant bike to exceed Merckx’s mark by just 10 meters.

Frank Carpenter sold the business and retired at about this time. The Carpenter marque still carried a cache with the racing fraternity so continued as a range offered by Colin Capes Cycles, the retail arm of Swindon Cycles. see CC7274.

After 5 or more decades of small incremental improvements in bike design, the world of the steel-framed bike was suddenly disrupted by a period of untrammelled experimentation, opened up by the use of exotic new materials. Titanium components had been pioneered on Merckx’s hour bike, more appeared. A new emphasis on aerodynamics was enabled by the use of carbon fibre. Frank might have watched on colour TV as Greg LeMond time-trialled to his last-gasp 1989 Tour win with aero bars, helmet and a disc wheel, ushering in this new era.

After 5 or more decades of small incremental improvements in bike design, the world of the steel-framed bike was suddenly disrupted by a period of untrammelled experimentation, opened up by the use of exotic new materials. Titanium components had been pioneered on Merckx’s hour bike, more appeared. A new emphasis on aerodynamics was enabled by the use of carbon fibre. Frank might have watched on colour TV as Greg LeMond time-trialled to his last-gasp 1989 Tour win with aero bars, helmet and a disc wheel, ushering in this new era.

1990 The world had moved on. Frank saw out his last days in Worthing, eventually passing away in May 1990 at the age of 87.